Abstract

Introduction

It was postulated that antibiotics including macrolides could be used for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease but recent studies showed that macrolides increase the cardiovascular risk. We aimed to review the evidence of cardiovascular risk associated with macrolides regarding duration of effect and risk factors; and to explore the potential effect of statins for the prevention of cardiovascular events as a result of macrolide use.

Methods

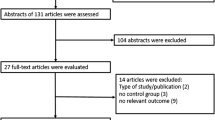

Several electronic databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library) were searched to identify eligible studies. Observational studies and randomized controlled trials that investigated the association between macrolides and cardiovascular events in adults aged ≥18 years were included. A meta-analysis was conducted to investigate the short- and long-term risks of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and stroke. Methodological quality was assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa scale and the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool. The body of evidence was evaluated by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation guidelines.

Results

Observational studies were found to have a short-term risk of cardiovascular outcomes including cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmia associated with macrolides but no risk was found in randomized controlled trials. However, no association for long-term risk (ranging from >30 days to >3 years) was observed in observational studies or randomized controlled trials.

Limitations

The included studies reported different units of denominators for absolute risk and used different outcome definitions, which might increase the heterogeneity.

Conclusions

More studies are required to investigate the short-term cardiovascular outcomes associated with different types of macrolides. Future studies are warranted to evaluate the effect of statins for preventing excess acute cardiovascular events associated with clarithromycin or other macrolides.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Camm AJ, Fox KM. Chlamydia pneumonia (and other infective agents) in atherosclerosis and acute coronary syndromes: how good is the evidence? Eur Heart J. 2000;21(13):1046–51.

Anderson JL, Muhlestein JB. Antibiotic trials for coronary heart disease. Tex Heart Inst J. 2004;31(1):33–8.

Gurfinkel E, Bozovich G, Beck E, et al. Treatment with the antibiotic roxithromycin in patients with acute non-Q-wave coronary syndromes: the final report of the ROXIS Study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20(2):121–7.

Muhlestein JB, Anderson JL, Carlquist JF, et al. Randomized secondary prevention trial of azithromycin in patients with coronary artery disease: primary clinical results of the ACADEMIC study. Circulation. 2000;102(15):1755–60.

Neumann F, Kastrati A, Miethke T, et al. Treatment of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection with roxithromycin and effect on neointima proliferation after coronary stent placement (ISAR-3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9274):2085–9.

Zahn R, Schneider S, Frilling B, et al. Antibiotic therapy after acute myocardial infarction: a prospective randomized study. Circulation. 2003;107(9):1253–9.

Cercek B, Shah PK, Noc M, et al. Effect of short-term treatment with azithromycin on recurrent ischaemic events in patients with acute coronary syndrome in the Azithromycin in Acute Coronary Syndrome (AZACS) trial: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):809–13.

O’Connor CM, Dunne MW, Pfeffer MA, et al. Azithromycin for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease events: the WIZARD study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1459–66.

Sinisalo J, Mattila K, Valtonen V, et al. Effect of 3 months of antimicrobial treatment with clarithromycin in acute non-q-wave coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2002;105(13):1555–60.

Andraws R, Berger JS, Brown DL. Effects of antibiotic therapy on outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2641–7.

Jespersen CM, Als-Nielsen B, Damgaard M, et al. Randomised placebo controlled multicentre trial to assess short term clarithromycin for patients with stable coronary heart disease: CLARICOR trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7532):22–7.

Svanstrom H, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of clarithromycin and roxithromycin and risk of cardiac death: cohort study. BMJ. 2014;349:g4930.

Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, et al. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20):1881–90.

Ray WA, Murray KT, Meredith S, et al. Oral erythromycin and the risk of sudden death from cardiac causes. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(11):1089–96.

Schembri S, Williamson PA, Short PM, et al. Cardiovascular events after clarithromycin use in lower respiratory tract infections: analysis of two prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2013;346:f1235.

Gluud C, Als-Nielsen B, Damgaard M, et al. Clarithromycin for 2 weeks for stable coronary heart disease: 6-year follow-up of the CLARICOR randomized trial and updated meta-analysis of antibiotics for coronary heart disease. Cardiology. 2008;111(4):280–7.

Winkel P, Hilden J, Fischer Hansen J, et al. Excess sudden cardiac deaths after short-term clarithromycin administration in the CLARICOR trial: why is this so, and why are statins protective? Cardiology. 2011;118(1):63–7.

Jensen GB, Hilden J, Als-Nielsen B, et al. Statin treatment prevents increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality associated with clarithromycin in patients with stable coronary heart disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010;55(2):123–8.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Jespersen CM, Kolmos HJ, Frydendall N, et al. Compliance with and short-term adverse events from clarithromycin versus placebo in patients with stable coronary heart disease: the CLARICOR trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64(2):411–5.

Winkel P, Hilden J, Hansen JF, et al. Clarithromycin for stable coronary heart disease increases all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and cerebrovascular morbidity over 10 years in the CLARICOR randomised, blinded clinical trial. Int J Cardiol. 2015;182:459–65.

Berni E, de Voogd H, Halcox JP, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events, arrhythmia and all-cause mortality associated with clarithromycin versus alternative antibiotics prescribed for respiratory tract infections: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e013398.

Jolly K, Gammage MD, Cheng KK, et al. Sudden death in patients receiving drugs tending to prolong the QT interval. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68(5):743–51.

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction: GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–94.

Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed 8 Feb 2017.

Coloma PM, Schuemie MJ, Trifiro G, et al. Drug-induced acute myocardial infarction: identifying ‘prime suspects’ from electronic healthcare records-based surveillance system. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72148.

Kim W, Jeong M, Hong Y, et al. A randomized trial for the secondary prevention by azithromycin in Korean patients with acute coronary syndrome after percutaneous coronary intervention. Korean Circ J. 2004;34(8):743–51.

De Bruin ML, Langendijk PNJ, Koopmans RP, et al. In-hospital cardiac arrest is associated with use of non-antiarrhythmic QTc-prolonging drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(2):216–23.

Straus SMJM, Sturkenboom MCJM, Bleumink GS, et al. Non-cardiac QTc-prolonging drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(19):2007–12.

Van Noord C, Sturkenboom MCJM, Straus SMJM, et al. Non-cardiovascular drugs that inhibit hERG-encoded potassium channels and risk of sudden cardiac death. Heart. 2011;97(3):215–20.

Zambon A, Polo Friz H, Contiero P, Corrao G. Effect of macrolide and fluoroquinolone antibacterials on the risk of ventricular arrhythmia and cardiac arrest: an observational study in Italy using case-control, case-crossover and case-time-control designs. Drug Saf. 2009;32(2):159–67.

Chou HW, Wang JL, Chang CH, et al. Risks of cardiac arrhythmia and mortality among patients using new-generation macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitors: a Taiwanese nationwide study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(4):566–77.

Mortensen EM, Halm EA, Pugh MJ, et al. Association of azithromycin with mortality and cardiovascular events among older patients hospitalized with pneumonia. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2199–208.

Rao GA, Mann JR, Shoaibi A, et al. Azithromycin and levofloxacin use and increased risk of cardiac arrhythmia and death. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):121–7.

Svanstrom H, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of azithromycin and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1704–12.

Trac MH, McArthur E, Jandoc R, et al. Macrolide antibiotics and the risk of ventricular arrhythmia in older adults. CMAJ. 2016;188(7):E120–9.

Wong AY, Root A, Douglas IJ, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes associated with use of clarithromycin: population based study. BMJ. 2016;352:h6926.

Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Mylona V, Antonopoulou A, et al. Effect of clarithromycin in patients with suspected Gram-negative sepsis: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(4):1111–8.

Gurfinkel E, Bozovich G, Daroca A, et al. Randomised trial of roxithromycin in non-Q-wave coronary syndromes: ROXIS Pilot Study. Lancet. 1997;350(9075):404–7.

Leowattana W, Bhuripanyo K, Singhaviranon L, et al. Roxithromycin in prevention of acute coronary syndrome associated with Chlamydia pneumoniae infection: a randomized placebo controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 2001;84(Suppl. 3):S669–75.

Johnston SL, Szigeti M, Cross M, et al. Azithromycin for acute exacerbations of asthma: the AZALEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1630–7.

Andersen SS, Hansen ML, Norgaard ML, et al. Clarithromycin use and risk of death in patients with ischemic heart disease. Cardiology. 2010;116(2):89–97.

Ostergaard L, Sorensen HT, Lindholt J, et al. Risk of hospitalization for cardiovascular disease after use of macrolides and penicillins: a comparative prospective cohort study. J Infect Dis. 2001;183(11):1625–30.

Root AA, Wong AY, Ghebremichael-Weldeselassie Y, et al. Evaluation of the risk of cardiovascular events with clarithromycin using both propensity score and self-controlled study designs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(2):512–21.

Woolley IJ, Li X, Jacobson LP, et al. Macrolide use and the risk of vascular disease in HIV-infected men in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Sex Health. 2007;4(2):111–9.

Grayston JT, Kronmal RA, Jackson LA, et al. Azithromycin for the secondary prevention of coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(16):1637–45.

Stone AF, Mendall MA, Kaski JC, et al. Effect of treatment for Chlamydia pneumoniae and Helicobacter pylori on markers of inflammation and cardiac events in patients with acute coronary syndromes: South Thames Trial of Antibiotics in Myocardial Infarction and Unstable Angina (STAMINA). Circulation. 2002;106(10):1219–23.

Vainas T, Stassen FR, Schurink GW, et al. Secondary prevention of atherosclerosis through chlamydia pneumoniae eradication (SPACE Trial): a randomised clinical trial in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29(4):403–11.

Berg HF, Maraha B, Scheffer GJ, et al. Treatment with clarithromycin prior to coronary artery bypass graft surgery does not prevent subsequent cardiac events. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(3):358–65.

Joensen JB, Juul S, Henneberg E, et al. Can long-term antibiotic treatment prevent progression of peripheral arterial occlusive disease? A large, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196(2):937–42.

Jackson LA, Smith NL, Heckbert SR, et al. Lack of association between first myocardial infarction and past use of erythromycin, tetracycline, or doxycycline. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5(2):281–4.

Jackson LA, Smith NL, Heckbert SR, et al. Past use of erythromycin, tetracycline, or doxycycline is not associated with risk of first myocardial infarction. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl. 3):S563–5.

Bjerrum L, Andersen M, Hallas J. Antibiotics active against Chlamydia do not reduce the risk of myocardial infarction. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(1):43–9.

Meier CR, Derby LE, Jick SS, et al. Antibiotics and risk of subsequent first-time acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1999;281(5):427–31.

Luchsinger JA, Pablos-Mendez A, Knirsch C, et al. Relation of antibiotic use to risk of myocardial infarction in the general population. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(1):18–21.

Corrao G, Botteri E, Bagnardi V, et al. Generating signals of drug-adverse effects from prescription databases and application to the risk of arrhythmia associated with antibacterials. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(1):31–40.

Mesgarpour B, Gouya G, Herkner H, et al. A population-based analysis of the risk of drug interaction between clarithromycin and statins for hospitalisation or death. Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14:131.

Patel AM, Shariff S, Bailey DG, et al. Statin toxicity from macrolide antibiotic coprescription: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(12):869–76.

Cheng YJ, Nie XY, Chen XM, et al. The role of macrolide antibiotics in increasing cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(20):2173–84.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AYW, EWC, AJW, and IW were responsible for the conception and design of the study. AYW was responsible for the process for selecting the study including screening. AYW and SA determined the eligibility and inclusion of studies in the systematic review and meta-analysis, extracted the data, and performed the quality assessment independently. AYW, EWC, SA, AJW, and IW contributed to the analysis and the drafting, revision, and final approval of the manuscript. All authors were responsible for interpretation of the data. AYW is the guarantor of the review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

EWC was funded by a Small Project Funding, Committee on Research and Conference Grants from the University of Hong Kong for this project (No. 201409176255). The sponsor had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the article; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

Angel Y. S. Wong, Esther W. Chan, Shweta Anand, Alan J. Worsley, and Ian C. K. Wong have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, A.Y.S., Chan, E.W., Anand, S. et al. Managing Cardiovascular Risk of Macrolides: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Drug Saf 40, 663–677 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0533-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0533-2